Patrick WintourDiplomatic editor

Storm Daniel was by no means the only factor behind the devastation wrought on the city of Derna

When the climate crisis meets a failed state, the outcome is the kind of disaster that Libya is witnessing in Derna.

Any city would have struggled with the extraordinary level of precipitation that Storm Daniel visited upon Libya’s northern coast. In its earlier, milder form, the storm caused severe damage in Greece before it crossed the Mediterranean.

Nevertheless, the extent of the devastation – a quarter of a city was swept into the sea in what is being described as Libya’s 9/11 – is also a function of the country’s failed politics.

After the bloody western-backed ousting of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, the country has mainly been governed by two rival administrations, one in Tripoli and the other in Tobruk, each supported by an assembly of rival external actors including Turkey, the UAE, Qatar, Egypt and Russia’s Wagner group.

Under Gaddafi’s pseudo-socialism in the late 1970s and 80s, the dictator dismantled oil-rich Libya’s private sector through the administration of state-owned companies, shattering the independent powerbase of the upper classes. “State enterprises became patronage networks,” explains Wolfram Lacher, the co-editor of a recently published collection of essays, Violence and Social Transformation in Libya.

Post-Gaddafi, the two sides have been similarly centralised. Ministers in the government of national unity, based in the west of the country, were nominated by militia. In the east, a relentless centralisation drive by the authoritarian head of the Libyan National Army, Gen Khalifa Haftar, and his family similarly ended up with numerous executives nominated by Haftar or his associates.

The two sides were at all-out war as recently as 2020. Hafter’s forces besieged Tripoli in a year-long failed military campaign to try to capture the capital in which thousands of people were killed. Then in 2022, the former leader of the eastern administration Fathi Bashagha tried to move his government into Tripoli before clashes between rival militias forced him to withdraw. This rumbling, mostly low-intensity conflict, requiring leaders to assuage their base with handouts, is the worst environment in which to make infrastructure investments that reap rewards only in the long term.

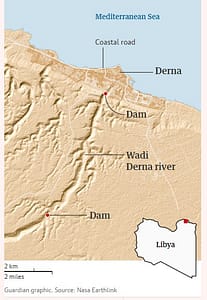

Bringing this context to Derna, the city that has long suffered since Gaddafi’s demise, either by being in the hands of Islamic State or since its recapture by Haftar in 2016, and infrastructure investment has always been at a premium. Haftar, whose secondary education was in the city, has also tried to keep close control of the Derna’s politics.