By Rachel Chang

From the park’s mountain peaks to its winding roads to its wood-panelled buildings, Chinese American history is everywhere in Yosemite – if you know where to look.

Hidden beyond the iconic Half Dome monolith, about a 90-minute drive north-east from Yosemite Valley, a quiet section of Yosemite National Park emerges. Here in Tuolumne Meadows, less-gazed-upon domes and peaks are served with a refreshing dose of serenity in the subalpine terrain. Lurking in the background, just out of view, is Sing Peak, rising 10,552ft from the park’s south-eastern corner.

“The way the topography is with certain ridge lines and perspectives, [Sing Peak] just gets hidden. But it’s on our park map – the one that millions of people receive,” said Yosemite park ranger Yenyen Chan, explaining that only 19 of the hundreds of peaks in Yosemite are listed on the map.

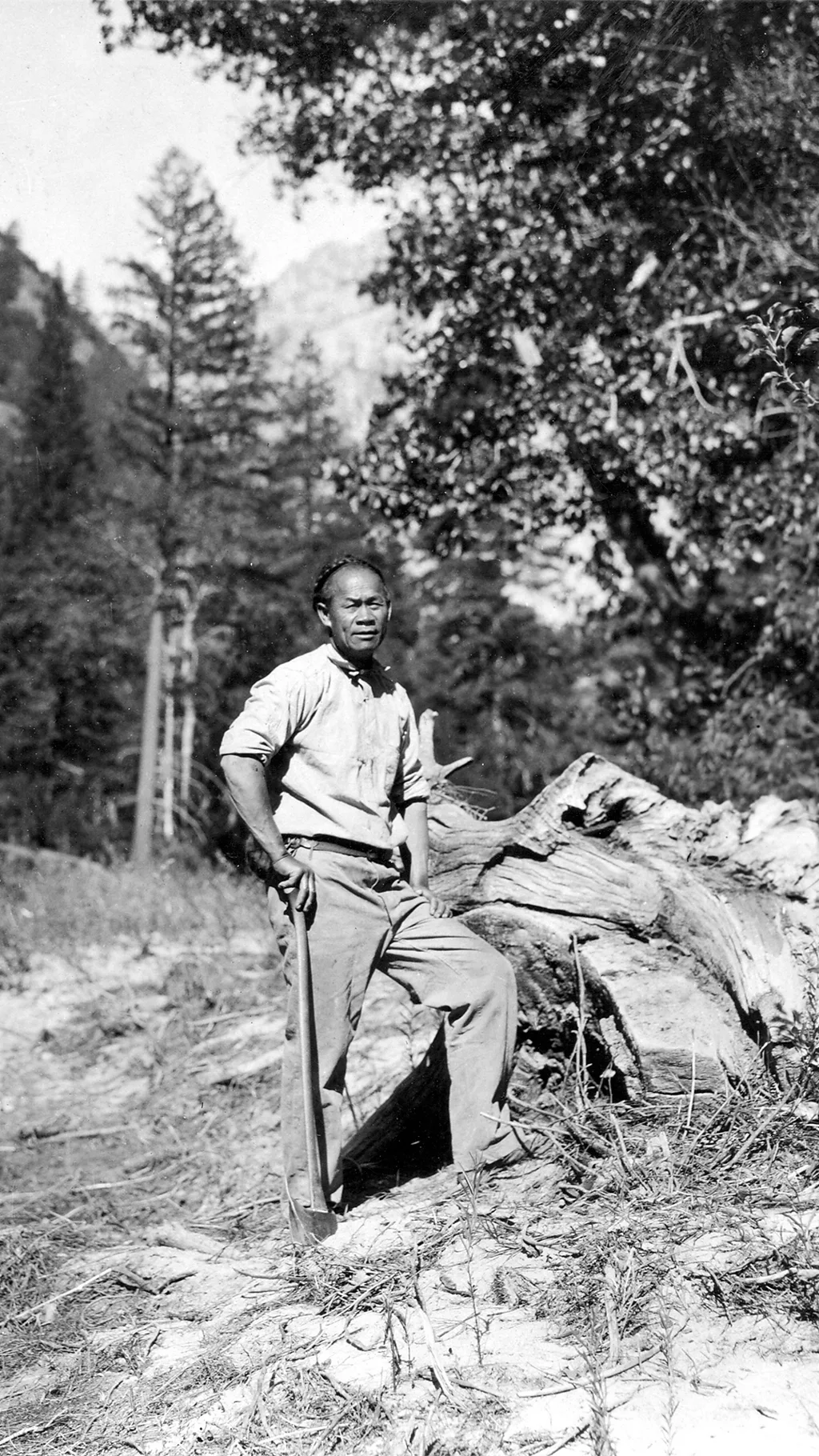

It’s somewhat symbolic that a massive summit named after Chinese American chef Tie Sing in 1899 has remained largely unrecognised in Yosemite for more than a century.

In fact, Chinese immigrants have long been part of Yosemite’s story, from building large parts of the park’s early infrastructure to running the kitchen and laundry services at the park’s 1856-built Victorian-style Wawona Hotel. Yet, their contributions have remained ignored.

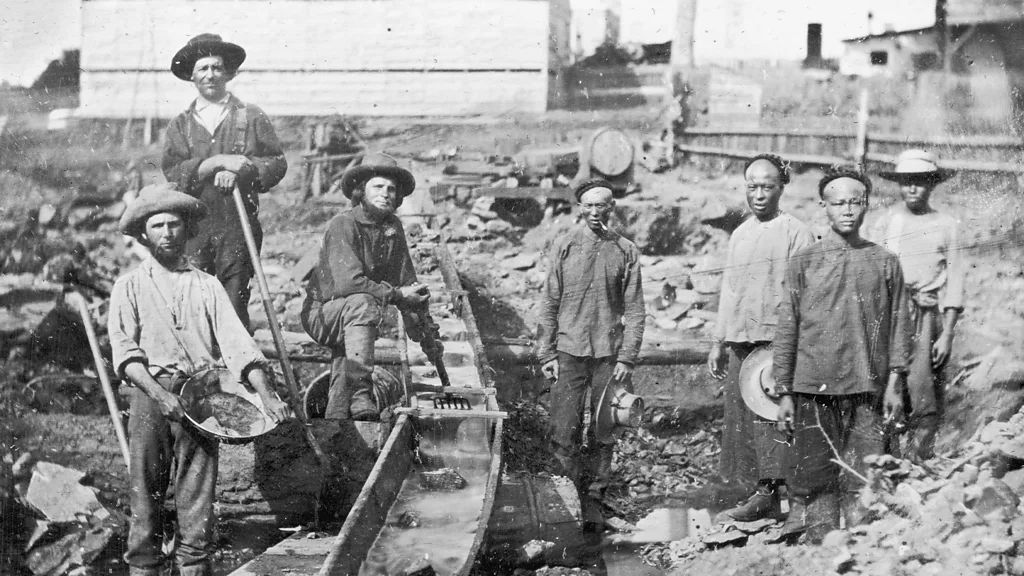

Yosemite’s Chinese American history has likely been buried because of the nation’s long history of anti-Asian sentiment and discrimination. The surge of Chinese who immigrated to California during the Gold Rush in the late 1840s were immediately slapped with a foreign miners tax in 1850 and a hefty $20 a month “non-citizens” fee. That forced many to find work in other industries, like hotels and railroads. But then came the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, banning Chinese labourers from entering the country, a policy that remained in place until 1943.

Chan, who has been a US Park Ranger since 2003, got her first hint of Yosemite’s Chinese American history in 1993 as a park intern, when her supervisor told her that the Chinese built the Tioga Road, which climbs above the valley and crosses the park from east to west back in 1882-83.

“I was like, ‘How come I had never heard of the Chinese being anywhere in the area, let alone this incredibly beautiful wilderness?'” she said. “I had no context and felt like very few people knew about it. When I tried digging into it, I could only find a little.”

So, during her downtime, she started researching on her own, scouring libraries throughout California for documents, photographs and any hints of early Chinese contributions to Yosemite. She found that a 56-mile stretch of the Great Sierra Wagon Road, which has mostly become today’s Tioga Road, was built by 250 Chinese American and 90 white labourers in a mere 130 days, according to one report.

Even prior to that, Wawona Hotel owner Henry Washburn had hired a crew of mostly Chinese immigrants, who constructed the Wawona Road around 1874. Working through harsh winter conditions and using handpicks, shovels, axes and blasting powder, the Chinese workers managed to complete the 23-mile road in 18 weeks. Visitors entering Yosemite through the south entrance on Highway 41 today still pass over parts of the road originally built by those workers.

Washburn also staffed his kitchen with Chinese immigrants, led by head chef Ah You, whom he hired in 1886. Though he ran the kitchen until 1910 and worked in the hotel a total of 47 years until 1933, he and the other Chinese workers were often kept out of sight.

Mark Twain even immortalised the diligence of California’s Chinese labourers in his 1872 travel book Roughing It, writing: “They are as industrious as the day is long… and a lazy one does not exist.”

Eventually, a mentor of Chan’s encouraged her to put together a seminar and all-day hike about the park’s Chinese American history. Among her findings was the background of the peak’s namesake Sing. But due to a lack of firsthand records and the unreliability of certain historical documents that were likely altered to protect Chinese workers against anti-Asian policies, Chan’s search proved challenging. Case in point: according to records, Sing was born in Nevada to Chinese immigrants. But Chan says Sing also had documents with another Chinese name and a wife and at least one child in Hong Kong. “We don’t know for sure,” she said.