Generative AI can involve citizens directly in decision-making, but not while developers’ incentives are only financial

The YouTube clip I return to most often is David Bowie being interviewed by Jeremy Paxman on Newsnight in 1999. Bowie is talking about what the internet might do: “I don’t think we’ve even seen the tip of the iceberg. I think that the potential of what the internet is going to do to society, both good and bad, is unimaginable. I think we’re on the cusp of something exhilarating and terrifying.”

“It’s just a tool, isn’t it?” condescends Paxman. “It’s an alien life form,” insists Bowie. “Is there life on Mars? Yes, and it’s just landed here.”

At the time of that Bowie interview I was writing a university dissertation titled Freedom of Speech in Cyberspace: the Challenge the Internet Poses to the Constitution of the United States. It was a heady time. The peak of internet utopia, with tech idealists promising that the decentralising nature of the internet would radically reform power dynamics, and democracy could be reborn.

Fast forward 25-odd years and we know the opposite has happened: truth and trust have been eroded, democracy has failed to reform for the digital age and the relationship between those in power and those who elect them is strained to breaking point. It’s at this moment that we are seeing the proliferation of generative AI, and understandably the response has been a mixture of hysteria and hope.

The hysteria about killer robots risks masking the real societal impacts that industrial revolutions inevitably have, sifting winners and losers, and disrupting ways of living in more subtle and sometimes pernicious ways. But there is hope for democracy in the AI revolution – if we put the right guardrails around it.

If we make AI work for democracy, then in 10 years’ time our information ecosystems could be vastly improved to support democratic decision-making. We could train AI to value verified information, and serve it in ways that make the most complex information more accessible to more people.

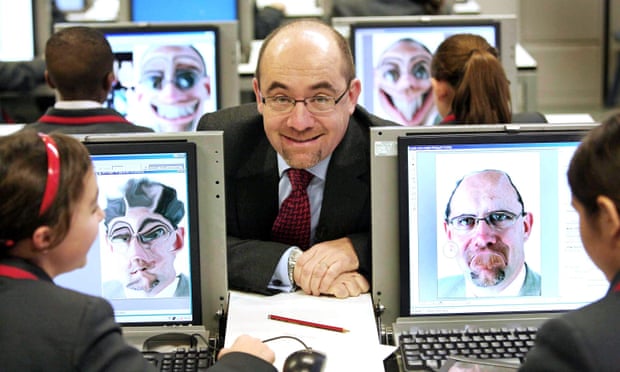

Politicians could be more trusted to do the right thing by people, because they’ve learned new ways to involve people in decision-making. AI citizens’ assemblies could help people and politicians to navigate through the trade-offs required to tackle the big problems. These concepts are not entirely outlandish. Polis is one such tool, developed in the US and used to shape policies most extensively in Taiwan, including to design regulation for Uber. Deceptively simple, Polis maps people’s views according to consensus, rather than division, and gives people options to suggest policy ideas. In the UK, we at Demos have worked with the Cabinet Office on Polis projects to engage experts and the public in the 2021 integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy. Andrew Gray, an independent candidate in July’s Selby and Ainsty byelection, is using it to power all his policies, declaring himself the first AI-powered politician.

In a decade’s time we could repair the relationship between state and citizen. It could facilitate dialogue between MPs and constituents, enabling elements of direct democracy to supplement our representative system. AI could also allow for the better use of citizens’ data to target public services, interventions and support people on a more human level. AI could be used to guide people to access help from the state.

But this will only happen if we make it happen. Because right now the incentives to develop generative AI are all commercial, with investors steering the development of the technology in ways that threaten to further leave democracy behind – not least because the talent, expertise and infrastructure follows the money, rather than where it could be used for common good.

The Labour peer Jim Knight, who has been close to the latest digital bills going through parliament, makes a startling point: there are four legislative processes regarding digital under way at the moment, if you include the AI white paper published earlier this year. None of them mention protecting or promoting democracy as an explicit aim. Instead, they are concerned with online safety, digital markets and data protection. Democracy is the elephant in the room.

Without focusing explicitly on the potential for AI to improve democracy – or at least do no harm – it will most probably corrupt. Distrusted information will proliferate, further eroding trust. But without explicitly updating our democracy to encompass more participatory activities that could be facilitated through these technologies, we will increasingly be left in a system that is centuries out of date, trying to govern in a world that moves at completely different speeds and in completely different ways. We have to learn this time.